One of the Jisc Research Data Champions, who is also a Research Data Champion at the University of Cambridge, Annemarie Eckes, writes about the results of a survey that she conducted on the practices of early career researchers around data management. To learn more about the experience and work of other Research Data Champions over the last year, have a look at their presentations.

Research Data Management is an important day-to-day activity for Scientists. Research output, collaborations and productivity depend on it. No surprise, then, that research data management has become a requirement for many grant applications, and a compulsory document to show many funders. Skills in data management are therefore essential for a good scientific career.

However, Early Career Researchers (ECRs) often lack training in research data managements and gain knowledge mostly by doing. ECRs’ are thus getting into bad habits when they should be learning best practices right from the get go of their PhD. This might reflect poorly on them in their post-doc or scientific career of choice, where collaboration increases and data management and integrity is of high importance.

What makes me say this? Well, I conducted a mixed-methods investigation of surveys and semi-structured interviews on the Research Data Management Practices of ECRs in the Department of Geography, Cambridge to find out about current strategies, awareness and training needs of my fellow PhD students.

The survey was circulated to PhD students at all stages of their PhD in the Department of Geography, Cambridge. Respondents had a period of two weeks in the beginning of July 2017 to submit their answers. Besides the survey, 1:1 semi-structured interviews were conducted to follow-up on the content of the questionnaire, but also to get a more detailed view on individual RDM stories. Trends in the surveys were discussed, alongside with the interviewee’s individual data management strategies and their preferred method of training/information delivery.

Survey Results

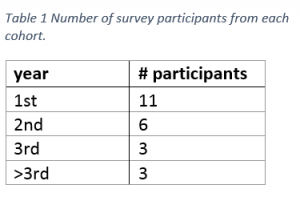

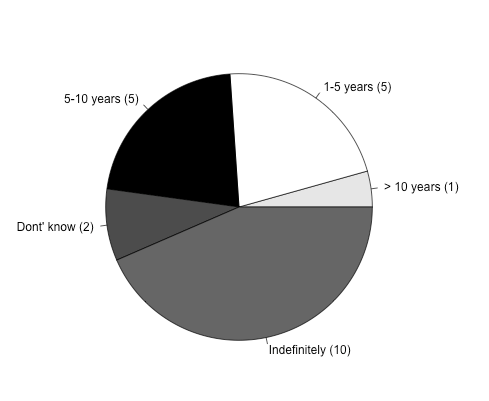

A total of 23 PhD students responded to the survey. Table 1 breaks down the number of participants of each cohort representing year groups. This section reports some of the results and is divided into RDM, FAIR principles and Training.

Data types generated

The data types used in the participants’ projects in the department is diverse, varying from GIS data sources, audio data from interviews, textual documents from ethnographies or transcribed interviews, to computer code and meteorological data, images and scanned documents. The size of the average data file varies substantially between KBs and GBs. A substantial number of participants did not know the average file size (results not shown).

Data storage and backup

All ECRs participating at this survey maintain a backup of their data, of which the majority (19 respondents) have one or two back-ups (see figure 2). Back-up frequency varies between more frequently than monthly and weekly (Data not shown).

Fair Principles

Data longevity and storage

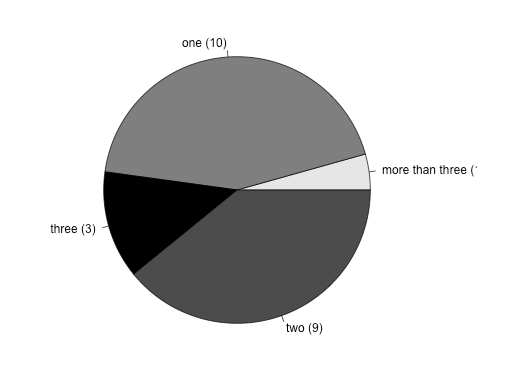

The majority of participants want research data to be stored indefinitely (10), followed by 5-10 years (5) and 1-5 years (5).

Most of the respondents reported that their data would not be in a shape to seamlessly work with analysis software (data not shown).

Data Sharing

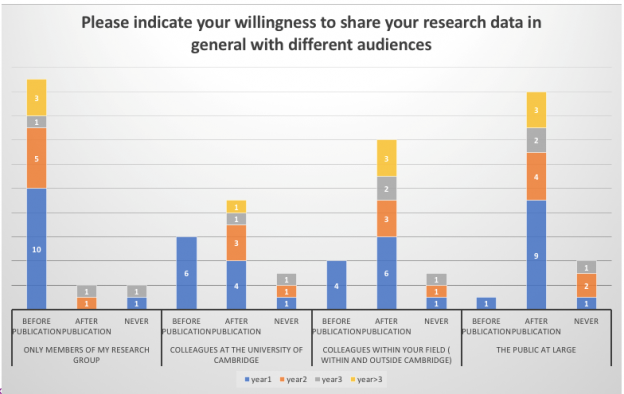

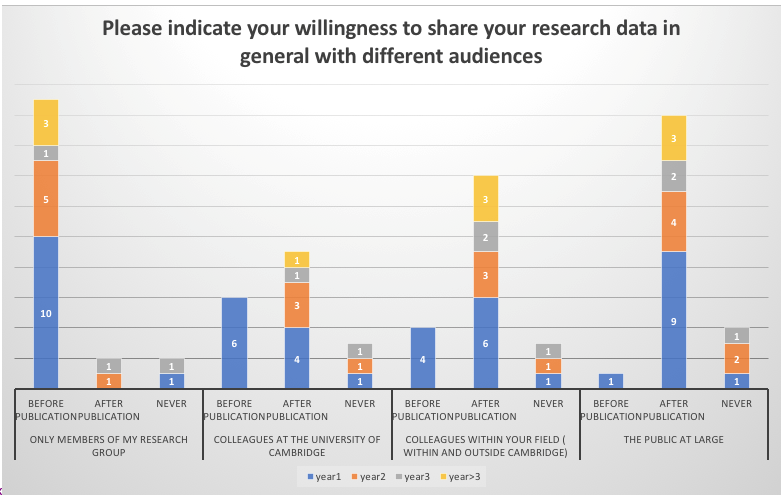

Willingness to share research data with other research groups or the public at large increases after the data has been published. A large majority of participants are willing to share unpublished research data within the research group. Willingness to share the data with colleagues within the field is higher than willingness to share with colleagues from the same university. Respondents answering that they would “never” share their data commonly explained this with their data being confidential and that they “would break ethical standards if [they] shared it”.

Training needs

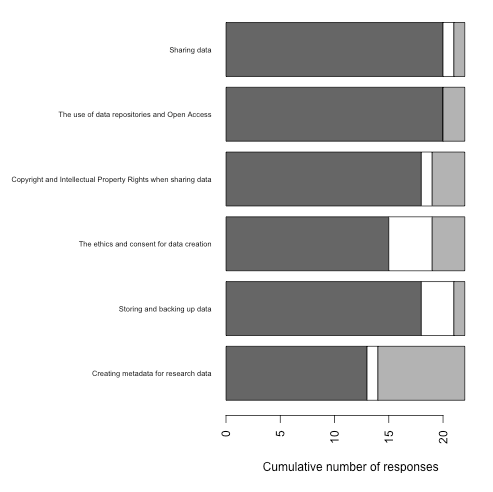

73% of the participants reported that they had never received any training in RDM. When asked what kind of training would be useful, interest is highest in training on sharing data, and the use of data repository and Open Access, followed by intellectual property rights when sharing data and the storing and backing up of data. The least interest is in Creating metadata. The need for training is nevertheless high, with all categories receiving more than 50% in every category. At the same time the survey results also show that students that are progressing towards the end of their PhD (category “3rd” and “> 3rd “) feel prepared to manage their research data (data not shown).

Discussion

The diverse landscape of data types reflects the diversity in methods which are applied in a broad subject such as Geography. This also leads to a wide range in average data file sizes that ECRs work with.

Research Data Management by ECRs

Despite no training in RDM, 100% of the students towards the end of their PhD (cohort “3rd” and “> 3rd”) report that they feel prepared to manage their research data in the future. However, at interview, participants stated that, looking back, they would have profited from training or guidance. Indeed, during one interview one student explicitly stated that “[the lack of experience in RDM] slowed me down”. Asked what that person would do different if the PhD could be repeated: “[I] would think about things more before I started fieldwork”. Therefore, while this “learning by doing” approach does seem to leave PhD students feeling adequately prepared for their research career, earlier training could improve their productivity, output and overall PhD experience.

Overall, all students state that they back up their data and do this in a more or less regular and frequent manner.

When interviewed, a student said that as s/he “learned as [they] went a long […] [data management was] not done it the best way.” In contrast, a student in physical geography, whose project involves writing computer code reported that research data management is intrinsic to the work and therefore “necessary but easy”. Data management was already part of this student’s routine practice, whereas the other student reported that the subject and methods diffed to their MSc and BSc as such that their previous experience was of no help. Whether this reported difference in level of research data management is intrinsic to the discipline (humanities vs. physical geography) or the individual cannot be answered here.

FAIR

Willingness to share published and unpublished data differs among the ECR cohort groups. First year students as opposed to the other cohorts seem to be more willing to share data before publication. Why this outline of a trend is not seen in the upper cohorts is not clear. This difference between first years and other cohorts might be caused by a change in view of first year ERCs once they have slaved over collecting data as a researcher for a lengthy period of time, in comparison to our light hearted and jolly first year selves. Another reason might be that more recent ECR generations have been exposed to the developing Open Research viewpoint. If this were the case, we can hope that the future generations of scientists would generally be more open to the principles of data sharing and open Data. However, more research would be needed to assess the impact on Open Data on early vs. later generations of ECRs.

Training interest in areas for FAIR and open data is high for all cohorts (Figure 5.)

Other FAIR principles are more or less represented in ECRs day-to day RDM practices. The majority of students reported that other people would be able to easily navigate their PhD project without any help. Further, 70% reports that they keep notes on where the data was from or how it was generated. However, 35 % report that they don’t always keep notes on how they edited the data (READMEs), while acknowledging that this is important practice .

While most students unconsciously practice FAIR principles to a degree, when asked explicitly the interviewees were unaware of the formalisation of the FAIR principles. Thus, while FAIR principles are rather pronounced in the scientific world, the PhD students in my study are unaware of them.

Training

Training courses on RDM and FAIR principles have been found to be in need. An in-depth standard data management course may be hard in a Department such as Geography due to the diversity of data types and methods that are applied, each with their special requirements. General courses covering the principles of RDM were given by me, supported by the Cambridge OSC team and Jisc. The number of participants was generally low, which reflects other Cambridge Data Champions’ experience of giving data management workshops. We hypothesised that general RDM courses, might discourage attendance as the utility of RDM cannot be directly linked with the attendee’s personal scientific problem. Nevertheless, the workshop attendee’s thought the course was useful for them. While this shows that the content, even though general seemed to be useful, the question remains whether advertisement from our side or disinterest/too much other work lead to the low attendance numbers. My and other Data Champions’ experience is that attendees found the activities very useful, which would indicate that advertisement strategies should be reviewed.

While low numbers on the department level, the depth of RDM training, alongside with the way it is advertised the survey did suggest that ECRs are willing to attend RDM-related training workshops.

Conclusion

This survey reports ECRs’ RDM skills and awareness of FAIR principles, along with training needs. RDM skills in the results presented here show that data backup and documentation of the origin of the data is largely performed. ECRs seem to struggle with documenting changes with their data, or seamlessly integrate them into analysis tools.

Participants at the end of their PhD report that they feel prepared for doing RDM beyond their PhD. Nevertheless, the majority state that they would have profited from some training, to avoid the oft ‘learn bad practice by doing it wrong’ approach.

Survey results are accessible from the Apollo repository from the end of May: https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.18831

About the author: Annemarie Eckes is a PhD student in the Department of Geography at Cambridge University. She is also one of the Jisc Research Data Champions. You can follow her work and updates on twitter @AnnehEckes.

About the author: Annemarie Eckes is a PhD student in the Department of Geography at Cambridge University. She is also one of the Jisc Research Data Champions. You can follow her work and updates on twitter @AnnehEckes.