On World Preservation Day 2019 we are delighted to publish a case study from a team at the University of St Andrews. Sean Rippington (Digital Archives and Copyright Manager, University Library), Federica Fina (Data Scientist, Research and Innovation Services) and Anna Clements, Head of Digital Research, Research and Innovation Services took part as a pilot in Jisc’s research data shared service developments, specifically seeking to pilot institutional digital preservation.

The team take a detailed look at the project, their participation in it and the systems they tested. Their experience was broadly positive, particularly with respect to the networks they built and the part that being a pilot for Jisc has played in raising the profile of digital preservation across the University.

1. Why Jisc RDSS?

There has been some dedicated digital preservation work in the Special Collections Division of the University of St Andrews Library since 2014. This has been limited to what individuals can achieve using free or low-cost tools. This is fine if you’re content to work with relatively small amounts of data, and can accept what might be called basic or ‘low level’ preservation (as defined, for example, by the NDSA levels of preservation). However, we have ambitions to scale up the volume of what we preserve, to include a wider range of content such as research data and e-theses, and to achieve a ‘higher level’ or standard of preservation.

There are systems in the marketplace intended to help with these ambitions – however, the costs of procuring, maintaining, developing and staffing these systems were prohibitive when we first explored them between 2014-16.

We were attracted to the Jisc Research Data Shared Services pilot project, launched January 2016 (now in production as the Jisc Open Research Hub) because it potentially offered:

- Economies of scale, reducing the initial procurement and ongoing maintenance costs of a digital preservation system

- Additional development work likely to be of value to us, including tools for automatically moving data between common HE systems and preservation systems, and strong reporting features

- A community of digital preservation practitioners at HE institutions working on similar problems, able to share good practice and ideas

- A new voice for digital preservation advocacy for HE institutions.

While there were no promises that the pilot would be able to achieve these things, senior management at the University agreed that we should engage with the project and work with Jisc and other pilot institutions to learn from others and help shape the final service.

First steps

At the start of the pilot we were invited to submit to Jisc a list of requirements for a digital preservation system. The two products in the procurement framework, Archivematica and Preservica, would then be scored against the list and we would be assigned the system deemed to be the best fit for us. However, this process proved to be of limited value as:

- we probably didn’t have a good sense of our requirements at the start of the project

- there would probably be emerging requirements as we worked out more precisely want we wanted to preserve, and why

- understanding the manner in which a requirement is fulfilled is important, not just a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer

We also found that the systems scored pretty evenly in the end, so the requirements list was not that useful in choosing between the systems by itself.

In addition, we knew that digital preservation was more than just a problem for research data, and that there would be all sorts of different digital stuff, managed in different systems across the university, that ought to be included in any digital preservation planning. Many other pilots had the same opinion.

Jisc therefore agreed to provide us (and some other pilots) with access to both systems, so we could get a better sense of how the products compare. We were also invited to run dummy data through the systems to see how they might work for our different use cases, not just for research data. We were encouraged to engage with the existing user communities for both products too.

The Jisc RDSS Service Community

Jisc ran a series of events for pilot members – these started with a lot of enthusiasm and possibly, perhaps inevitably, ran out of steam a bit towards the end. These typically involved updates on the status of the project and some sharing of pilot experiences.

We met a lot of staff from other HE institutions of many different types at these events – a conscious choice from Jisc when selecting pilots. It was reassuring (or perhaps worrying!) that most institutions were broadly at the same stage as us, being somewhere between ‘thinking about digital preservation’ and ‘trying to procure a digital preservation solution’. I think all were still trying to reach some consensus about what digital preservation was, what it might look like, and where our efforts needed to be focussed. It was also noticeable that there was no correlation between the institution’s ‘status’ in terms of age or THE ranking, and its progress on the digital preservation journey.

Related preservation projects

Jisc also funded a related project for the University of Westminster to explore the archival and records management aspects of digital preservation. Attending an event underpinning this project formed a particular highlight for us, and it would be great to see Jisc funding more of these kinds of one-off events relating to the JORH – making the day focussed on a narrow topic really helped.

We also formed an informal sub-group of pilot members with similar goals, including staff from the universities of Lancaster and York. This proved fruitful, but turnover in staff made it difficult to maintain – a reminder that networks and communities can be as difficult to sustain as digital objects.

Latterly we also spoke to colleagues at the University of Glasgow who also joined the project and documented their digital preservation experiences.

Noticeable across these events was a welcome openness and willingness from colleagues at different universities to discuss their hopes and fears relating to digital preservation. Local resistance to change, ineffective advocacy for funding, lack of clear strategic vision in general and for digital services in particular, were often cited as obstacles to implementing library-based digital preservation systems.

Also noticeable was that having done even the smallest amount of work on a particular issue, or even expressing an opinion on it, can see you put forward as an expert on the topic – exciting and scary and the same time!

So great credit goes to those willing to talk through their challenges and questions in public with the hope of advancing community knowledge – though I’ve found that small group discussions undertaken in good faith are preferable to publishing works in progress online, with all that entails.

Preservation workflows

There were lots of discussions between the pilots, Jisc, and the preservation system vendors about what a research data preservation workflow might look like – you can read the Archivematica/Arkivum perspective on this.

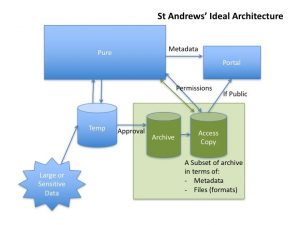

For our research data, we liked the idea of having the preservation system situated early on in the workflow, and using it to generate the access versions of the data and metadata for use on our web portal. This would allow us to take advantage of the preservation system’s ability to generate copies of data in more usable file formats.

Fig 1 A proposed workflow for research data preservation and access at St Andrews

This was counter to our initial instinct that preservation actions might occur after the business of receiving and making research data accessible had already happened, or that it was the role of a preservation system to effectively back up the contents of our access portal.

Automation and reporting

There was some discussion of the RDSS being fully automated from ingest to access – we can see why this is attractive, especially to institutions with no specialist digital preservation staff. However, we were not convinced about the possibility of fully automating our preservation processes given the heterogeneity of the size and form of our collections and their metadata. On the other hand, some level of automation will be a necessity given the scale of the data we want to preserve.

We felt that our best bet was to argue for a largely automated system with strong reporting features allowing us to focus our limited staff time on manual intervention in the areas of most need.

This needed to be combined with training and guidance for data creators to make sure that they can produce data and metadata that lends itself to automated processing (e.g. using consistent structured and standard, high quality metadata) – all while acknowledging that pushing the manual, often tedious work of digital preservation back to data creators was basically undesirable and unlikely to have a high success rate based on previous experience. After all, as archivists, librarians and data scientists, we should provide a preservation service to our users, not the other way around.

Unfortunately, the reporting/dashboard functionality within RDSS was not completed for testing by the end of the project, so if we are to have this in the short term it will not be through this service. The preservation systems do have their own reporting functionality that could be used in the interim.

Sustainability in the long term

There’s a principle in digital preservation that keeping your system as simple as possible will increase your chances of sustaining it in the long term.

However, both systems seemed to have somewhat over-complicated functionality for our needs, which is probably inevitable when using an off the shelf product intended to cater to many different users and use cases. This presents the difficulty in knowing what functions you should use, how, and when – this is no minor task! With either preservation system, it would certainly be worth taking time to understand the difference between what you really need, and what comes out of the box – though of course many users will not have the time or expertise to do this.

We also noted that the individual components of the systems may be maintained by specific third party communities or developers, which adds external dependency risks that you will have to be aware of, even if you aren’t managing them directly.

On top of that, we had the additional complication of managing the system via Jisc, which created additional lines of communication and potential for confusion over who was responsible for what – an issue that came up a few times during the pilot.

So, making use of a digital preservation infrastructure provided by a third party could have many benefits, but you may have to trade this off against greater complexities in relationship management and additional external dependencies.

Developing adaptors

One of the most attractive elements of the RDSS was the promise to develop ‘adaptors’ – tools for automatically transferring data from a live system to a preservation system using APIs. This could go some way to partially automating ingest, making the preservation of large volumes of data more viable.

There were some caveats – it wouldn’t be practical to develop adaptors for systems that are not widely used across the sector; not all of the data we want to preserve is held in systems with APIs; and the whole thing only really works if your data are consistently structured and of good quality to start with.

We agreed to test adaptors for Pure, which we use to store our research data (amongst other things), and DSpace, the repository system we use for storing theses and open access publications.

The testing of these adaptors was somewhat complicated by the fact that Pure is a proprietary system. Whilst it has a very extensive API with which the Jisc developers could work to pick up metadata and datafiles, the terms of our licence meant we couldn’t provide Jisc with access to the front-end of Pure. We were able to do some testing in co-ordination with Jisc but this was time-consuming. Unfortunately, it took nearly 18 months of negotiations between ourselves, Jisc and Elsevier before Jisc were given access to their own Pure installation for testing. DSpace is open source and therefore easier to work with in this regard.

We found that there were some problems with the adaptors mangling data, which meant it was doing the opposite of automating preservation! The Pure-Preservica adaptor specially had some difficulty in handling zipped data sets (which account for 71% of our research data) and was automatically importing metadata records even when the actual data was unpublished and embargoed – meaning that we had a lot of collections in Preservica that didn’t contain any research data.

We continue to test the adaptors and feedback our responses to Jisc and hope that we can get functioning adaptors – this is something that would not just potentially benefit us, but also any other users of the same systems. As of the time of writing, we haven’t had access to adaptors for Pure-Archivematica or DSpace-Archivematica.

Storage solutions

For the pilot we were offered Amazon s3 cloud storage, which was procured via Jisc. Both Archivematica and Preservica are storage solution neutral, and can be configured to use either local or cloud storage, or a combination of the two.

We had no problems using the storage during the pilot, but would want to reconsider our options for storage, and our storage strategy, in any live system. We had used only small amounts of storage during the pilot and expect to require substantially more for any live system.

Where metadata gets managed

There was some discussion between pilots about how best to manage the metadata of preserved objects – the idea being that some metadata (e.g. descriptive metadata) might be better managed outside a preservation system, while other metadata (e.g. preservation metadata) might be better managed within.

Managing metadata outside a preservation system (e.g. in a collections management system) makes it easier to update and reduces the amount of processing required when ingesting data into a preservation system. On the other hand, it introduces the risk that metadata will become uncoupled with its associated preserved object, and that discrepancies in any duplicated metadata may emerge over time.

We did not reach a firm conclusion on this point, but making the Archival Information Package (AIP) as independently understandable as possible (e.g. by including all related metadata) would be desirable if this could be achieved without inducing unacceptable ‘metadata bloat’ within the AIP. This would support the general principle that you want to limit the number of external dependencies for an AIP as a form of preservation risk management.

Blue Sky Thinking

Throughout the project, we were encouraged to discuss possible future directions and functionality for the RDSS – understandable given the nature of a pilot project, but occasionally frustrating when it felt like attention was shifting from the more immediate ‘must have’ features to the ‘would be nice’ ones.

Probably the most developed of these is the Preservation Action Registry which is certainly promising, but which is definitely a ‘would be nice’ feature for us.

Other assorted ideas suggested throughout the pilot included:

- Some means for end users to report back on any problems with files

- Depositors getting some kind of feedback on when their data had been ‘preserved’

- Some form of ‘semi-current’ storage, with some basic preservation functionality and a PREMIS compliant log, for researchers to use before depositing the final version of their data. This could help with forward planning and assist early intervention with preservation problems

- Data peer review – encouraging peer review of data the same way as publications

- Data visualisations to better understand deposited data sets

- Reporting of potential preservation issues at the time of deposit by the researcher, using tools for identifying things like sensitive data, unidentifiable file formats, and IP issues. There are presumed benefits in working with depositors on these issues as early as possible.

- Possibilities for viewing and working with datasets in browser, rather than requiring download

- Automated dataset description and subject keyword generation using natural language processing

- Analysis of the state of UK research data management by studying metadata across the entire RDSS user base

- Proposals for preserving ‘big data’ that are unlikely to be managed in a repository

- Building a corpus of unidentified file formats from across users of the service, and using this to direct efforts in updating PRONOM and other file format registries.

2. Archivematica and Preservica compared

Introduction and Overview

Please note that the following comments are true of the specific instances of the systems provided to us by Jisc between Jan 2016 and Sep 2019, but may not be true of later versions or other implementations.

Both systems use broadly the same approach to preservation, and even the same tools in many cases. The philosophy underpinning both is informed by the Open Archival Information System Reference Model (OAIS), and involves:

- packaging up whatever you want to preserve with some descriptive information

- moving this package into the digital preservation system

- the system performing a series of more or less customisable actions to do things like identify and validate files, extract or generate metadata, produce copies in formats believed to be more sustainable, virus checks, and other tasks.

The systems can then also produce this package for an external user, with the precise form determined by a series of customisable rules. This might involve transforming the metadata to some new standard, or creating a copy of the files deemed to be better for access purposes. This process can be set up to happen automatically when you ingest the initial package, or on demand.

Whether or not OAIS-informed concepts and terminology are the best foundations for digital preservation systems is somewhat up for debate – but it’s the most recognised standard we have, and you can see the logic in building systems around it, even if it can seem frustrating or limiting.

The assumption for both systems is that users should plan for the content to outlive the system itself – not that there is any particular reason to think that Archivematica or Preservica are unsustainable, but simply acknowledging the unlikelihood of using any particular system in perpetuity. The use of standards should make it easier to move the contents to any future preservation system, but of course the devil is in the detail.

Archivematica is open source and has a well-established, international, growing user community, mostly in higher education institutions – though not all of that community are using it in a production setting.

The open source nature of the product allows you to see precisely what the system does and how it works, and to develop it to meet your needs. However, many users do not have the resources or skills to take direct advantage of this, and instead rely on Archivematica’s lead developer, Artefactual Systems to develop new updates, provide training, support and documentation. Being open source does in theory help mitigate against the risk against being ‘locked in’ in the event of the vendor going bust at short notice, or otherwise being dependent on one single organisation to make your system work. It may also be a good fit for institutions who value openness as a philosophy in general.

Although Archivematica is free to download, Jisc advised us that we should expect to pay more or less the same for either Archivematica or Preservica once support and development are factored in – in general it would be sensible for anyone considering Archivematica to budget for it as if it were proprietary software.

The community is well supported in the UK through the UK Archivematica User Group and mail list (which also has international counterparts), and there are local users to us in the Universities of Edinburgh and Strathclyde. There are also international Archivematica Camp events that function as a kind of user forum. Community members are invited to engage with the product wiki and github page – contributions could take the form of code, but user testing and documentation are also encouraged. Generally the level of user engagement is high, with good examples including the ‘Filling the Digital Preservation Gap’ report.

Preservica is a proprietary system developed from the Safety Deposit Box originally created for use by The National Archives. It has a well-established international user community, mostly in memory and education institutions, but with a significant presence in corporate and business, regional government and national archives. It’s a black box system, which is to say that the code is not published and you cannot see exactly how it works, though some individual components such as DROID, have been developed by the Preservica team and released to the public. The risk of vendor lock in is mitigated by the use of open APIs for export of data and metadata, though the reliance on the vendor for support in general represents a possible single point of failure.

The Preservica community is mostly focussed around the free annual User Group meeting and the Preservica Customer Portal. We also found that many Preservica users were happy to share their experiences on an informal one-to-one basis.

The focus of Archivematica is very much upon ingest. The assumption is that you would probably use other tools for managing the assets after this step, and for providing access. Preservica on the other hand might be thought of as an end-to-end digital asset management system, which majors on preservation activities.

In general we can see why an institution starting from scratch might see the value in a system like Preservica that offers a lot out of the box. An institution that already has a lot of the pieces in place, or which likes the flexibility of being able to swap out parts of systems, might prefer Archivematica.

Planning a preservation exit strategy

Assuming you want to preserve the contents of your digital preservation system forever, it’s important to have an exit strategy for any system you use – the idea being that you’re unlikely to use one particular system in perpetuity, and therefore migration of contents to successor digital preservation systems is inevitable.

Both systems make this easier to achieve by using documented standards where possible, and both vendors appear to be stable organisations unlikely to be unable to provide export support at short notice. The digital preservation system marketplace includes many options in addition to Archivematica and Preservica, so you may be able to find a reasonably like-for-like replacement if one were no longer viable.

At the time of writing, Preservica were unable to point us to an example of a real-life user’s exit strategy implementation, as no major user had moved away from the product. We attempted a sample exit strategy implementation ourselves but found that the bulk export function was disabled for Jisc users. We were advised that any exit would therefore have to be managed by Jisc, which is not ideal from a risk management perspective.

While we also failed to find a major real-life exit strategy implementation for Archivematica, the fact that the AIPs are already stored and understood independently of the system means you’re not dependent on the vendor for export, though some processing of the AIPs to make them suitable Submission Information Packages (SIPs) for a new system may be necessary.

We also judged that exiting the Jisc service in its entirety i.e. the preservation system and any additional services, could probably not be managed without Jisc’s support, and that it would be hard to find a single service that could replace it in all respects.

User expectations for access and ease of use

One of the possible requirements that emerged during the pilot was that some staff would like direct, read-only access to the archive to view material that their department had deposited. Not being able to provide this would most likely result in staff keeping local copies of files even if they were in the archive, which creates unnecessary duplication and costs for storage, and introduces the risk of discrepancies between different versions of files and their metadata across the institution.

This is a model of archives management counter to the gatekeeper philosophy we currently have for our physical paper archive, whereby access to the archive by users is mediated by professional archives staff – general users would never be given direct access to archives in storage. However, digital technology gives us new opportunities, and new user expectations, and we felt this was worth exploring.

Both systems can support the creation of different kinds of users with different access permissions, but I think it’s fair to say that Archivematica in its current incarnation is not intended for use by non-specialist browsers of digital archives, but rather for dedicated trained staff. There were discussions around development work being done to improve the Archivematica user interface but we didn’t see this during the pilot period.

Preservica on the other hand is more user friendly for browsing, has more of the functionality of a traditional Digital Asset Management (DAM) system, and has the look and feel of a Windows Explorer – all of which makes it more attractive for this kind of use.

How does ingest occur?

One fairly major difference between the two systems is that Archivematica effectively breaks the running of the microservices in to two distinct stages – a pre-ingest stage and an ingest stage, whereas Preservica runs them all at once during ingest.

This may not matter much to you – but it might be helpful if you like the idea of having some structured information about what you’re going to preserve before you actually put it in your preservation system.

This two-step ingest also allows you to spend some time appraising and rearranging the content between the steps, though there was some agreement among pilots that most of us would rather do the bulk of the appraisal and arrangement outside of Archivematica, if we were to do it at all.

File Format Identification

Identifying file formats is a cornerstone of the digital preservation approach taken by both systems, and much of their powerful preservation functionality is limited without this step. Unfortunately, failure to identify file formats was a recurring issue for both systems, most frequently when working with research data.

Both systems draw upon the same file format registry, PRONOM, which is highly useful but which receives limited support. Maintained by the UK National Archives, it has strong coverage of file formats used in central government contexts, but is patchier for those likely to be created across a research university. In any case, keeping it up to date with the file formats created during cutting-edge research is going to be difficult even if it were a core activity.

With sufficiently good reporting and additional staff resources, research data with unidentifiable files could be noted and the depositors contacted to gain information about the software used to create the files, which could be recorded as part of the deposit. The file format could then be formally identified and added to PRONOM. It would however be important to catch these unidentified file formats early while the depositors are more likely to have the time and resources to engage.

Both systems offer the possibility of rerunning file format identification tools at some point after ingest to take advantage of updates to PRONOM or other file format registries. We found this process a little easier in Preservica, which allows you to run this process over multiple collections at once, while Archivematica requires you to re-ingest individual collections. We also noted that Archivematica also requires partial or full re-ingest of AIPs for a number of other updates.

The Archival Information Package (AIP)

The AIP is the package of data and metadata that is created and stored. It is one of the key products of a digital preservation system. Though there are standards used in creating AIPs (such as the Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard (METS) and PREMIS), there is no such thing as a standard AIP, so we thought it worth looking at how equivalent Archivematica and Preservica AIPs compare. The structures of the AIPs in both systems are detailed in an E-Ark project report.

We found that the AIPs created in Archivematica had more verbose metadata and a more complicated structure than the ones we created in Preservica.

However, the construction and structure of the Archivematica AIPs is consistent, documented, machine-readable, and to an extent human readable – especially when using METSFlask. It is possible to view and understand them independently of the system, which may go some way towards avoiding system lock-in.

We talked to Artefactual about how you could reduce the size and complexity of the METS files in particular. Basically the three solutions were:

- Turn off some of the microservices (especially the File Information Tool Set (FITS), which has very large outputs) for certain content types

- Using PREMIS 3 instead of PREMIS 2, which is less repetitious

- Take PREMIS metadata out of METS and store using the Resource Description Framework (RDF) model instead

We haven’t really investigated this much beyond discussing it – you can read more about this work on the Archivematica wiki.

The Preservica AIP, while simpler and more human-readable, is only viewable within the system, stored by default in the proprietary XIP format. It can however be transformed to METS upon export as a Dissemination Information Package (DIP) instead.

Note that neither Archivematica nor Preservica AIPs currently conform to the E-Ark standard for AIPs, which has been put forward as a standard structure for AIPs intended to support system interoperability and sustainability.

Web and social media archiving

We have a need to preserve our own University website, and a desire to preserve some of our social media.

Preservica includes Heritrix for crawling websites and creating Web ARChive (warc) files, and is likely to soon include some means for capturing popular social media like Twitter. It’s also able to display warc files within the system as navigable websites.

Archivematica cannot create warc files but it can preserve them. It doesn’t have any ability to ingest social media without prior processing, though could presumably be developed with sufficient interest and funding.

At the end of pilot, we concluded that we would probably outsource web archiving entirely rather than attempt to achieve this in house using a digital preservation system, as it would probably be too complicated for us to manage.

SharePoint Integration

One of our major corporate records preservation use cases is exporting records from Sharepoint for ingest in to a preservation system – we therefore decided to investigate how this might work for Archivematica and Preservica.

We decided to use the strategy of exporting SharePoint sites, including their constituent files and supporting metadata, and ingesting them into preservation systems. SharePoint exports take the form of .cmp files, a kind of cabinet file that holds all your MS Office documents in the form of renamed .dat files. It also contains an xml manifest file with the original names and file extensions of all the .dat files.

We found that a .cmp file can be ingested into Archivematica, with the .dat files identified as their original format types. However the .dat files are not migrated to appropriate preservation formats, nor are any metadata extracted.

Some pre-processing of the .cmp file to rename and reinstate the file extensions of the .dat files improved things, allowing for some metadata extraction and making the AIP more human readable.

Preservica on the other hand is able to recognize a .cmp file as a SharePoint export, and uses the manifest xml file in the .cmp to rename and reinstate the filename extensions of the exported files. It is also able to recognise previously ingested files to prevent duplicating them during subsequent ingests.

Preservica are also working on new functionality that effectively harvests files from SharePoint sites using retention rules set up by the user. This is likely to be a more efficient and easier to automate approach.

How is encryption handled?

In light of GDPR and general security concerns, we were interested in how the two systems, and the Jisc service as a whole, deal with encryption.

For both systems, files can be encrypted at rest but must be unencrypted while being processed. Most of the preservation tools cannot work on encrypted files.

We had hoped to test the ability of the RDSS service to handle sensitive files, but this functionality wasn’t available before the end of the pilot period.

Scanning for viruses

We found that Archivematica’s default virus scanning software, Clam AV, was stalling our ingests due to a limit on the size of file it could handle. This was set at 42MB and can be increased by allocating more memory to the virus scanning container.

However the solution to this within the pilot was simply to turn off the virus checking function altogether – this might be a valid option in some situations but it’s something we’d want to reconsider in any production system!

Zip and other archive file formats

The ability of a preservation system to deal with archive file formats is an issue for us a significant percentage of our deposited research data takes the form of zips, nested zips, and/or non-zip archive files.

We found during the pilot that Preservica only seems to uncompress zip files – all the other archive file formats in our collections e.g. (e.g. rar, 7zip) were just treated as regular files and weren’t uncompressed. We also found that Preservica would only unzip the first level of nested zips. This limited the possibilities for file format identification, metadata extraction and format migration for the contents of those compressed files, and therefore much of the value of having them in a preservation system.

Archivematica on the other hand uncompressed all the types of archive file formats we tested, and uncompressed all nested files.

Are there options for ‘Big Data’?

‘Big data’ is being created at the University, and we were hoping that the RDSS service would provide some options for preserving these.

In the pilot, the size limit on datasets was 5GB and we were never demoed anything larger. Therefore we’re unclear how larger than average datasets would perform in either system when managed through the Jisc service.

As an interim solution, both systems allowed for the preservation of metadata about big data sets, if not necessarily the big data sets themselves.

Access to collections

We already have access systems in place for many of the types of data we want to preserve, so we weren’t really looking to the Jisc RDSS to provide solutions in this area. Nevertheless we were open to exploring how this might work in case we wanted to use the Jisc RDSS to provide access to collections in the future.

Archivematica is not intended as an access system – instead you are encouraged to produce DIPs for access via a separate system. Atom would be the most obvious for this as it shares a vendor, and there are several existing successful integrations of the two systems.

Preservica has a built in ‘Universal Access Viewer’ but we had only limited opportunities to explore this as pilots. It can also produce DIPs for other access systems.

3. The impact of being a pilot institution

Taking part in the pilot project has created some (hopefully lasting!) benefits for us as an institution. In the first instance, it provided a focus for our digital preservation activities, and encouraged the library to form a group of staff across several divisions dedicated to exploring the possibilities for digital preservation at St Andrews.

Assumptions about digital preservation

We’ve been forced to think about what precisely we want to preserve, why, where it is and how much work will be needed to prepare it for preservation. This work resulted in the creation of a digital asset register highlighting areas most at risk and suggesting priorities for ingest into a preservation system.

This is turn formed the basis of a business case for an institutional digital preservation system and associated staffing, underpinned by a vision of what a successful implementation might look like after 18 months, and in the longer term. We are also close to finalising a University-wide digital preservation policy, stating our institutional commitments and aspirations in this area.

We’ve had to rethink our assumptions about what a digital preservation system, and a digital preservation service, for the University might look like. We’ve moved from envisaging a library-focussed, archivist as gatekeeper model to one which is library-based but which serves a broader audience across the University, catering to a wider set of needs and expectations. We also understand the need for more effective data and records management at the University, with associated policies, training and guidance, to ensure that our digital content is easier to preserve.

Engagement across the UK

We also got the opportunity to engage with digital preservation experts and practitioners from libraries across the UK, which should form the basis of professional networks that can support our digital preservation efforts over the next few years.

In short, we think we’ve gained a better understanding of what our stakeholders need, what a solution might look like, and how we can get to where we need to be.

4. What next?

We submitted our internal business case for a digital preservation system for the University earlier this year. While the need for a system was accepted, the University requested that we develop an institutional-wide digital preservation policy before resubmitting an updated business case for consideration.

We therefore will not be going into production with the JORH, or any other digital preservation system, this year. However this is still the ambition in the short to medium term.

5. Conclusion

Sharing services offers a lot of benefits and should make high quality digital preservation more achievable for institutions with limited funding and/or IT support, but will only work if everyone involved shares a vision of what the service offers.

In the case of the Jisc RDSS, there was probably always some tension between the original research data focussed concept of the project and the wider applications we wished to put the system to.

In addition, as the project evolved, attention shifted away from a shared service that offered what we were originally hoping for, and more towards a general research data management service for HE institutions with no specialist staff. This included a significant amount of developer time being spent on creating a new repository platform – a perfectly valid way for the pilot project to evolve, which will result in a service likely to be of value to many, but which may not be the best fit for us.

Specifically, we were hoping for features like automated data transfer between our major systems and preservation system, powerful reporting on preservation actions, and the ability to preserve large and/or sensitive data sets – none of which we have been able to see at the time of writing. We also found that managing communications across the service, including its constituent vendors and subcontractors, was a lot of work.

Nevertheless, the experience was broadly positive, particularly with respect to the networks we have built and the part that the RDSS has played in raising the profile of digital preservation across the University. We hope to resubmit a business case for a digital preservation system in the next 12 months. If successful we will look to explore the market, including the JORH, for the solution that best fits our needs.